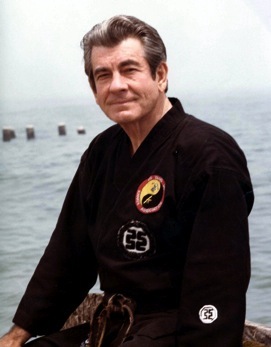

SHIHAN FOSTER REFLECTING ON FIFTY YEARS IN KARATE

BY AL GOMEZ, JUNE 1987

I didn’t start school until I was nine years old. I could already read and write when I started school because I learned at home. And, being weak and little, I had been bullied quite a bit. I figured I had to use my brain in order to fight my way through. I didn’t have enough sense of diplomacy to get around it where I could have. But then I began to study, and I remember I took Farmer Burn’s correspondence course in wrestling. I thought this was going to be “it” So, I did this and dynamic tension and so forth. When I started these exercises my health changed. I changed from a very weak person into a person who was very wiry.

At that time, boxing was the big thing. So I boxed quite a bit. I wish now that I had given more time to Karate, but I didn’t know it. There was a period of time when my father was pretty much an invalid. We had moved from the city out to a farm, and I was the oldest one in a big family. I had to take care of the cows and the farm in general, so I wasn’t able to play baseball, football or basketball because I didn’t have the time. But, if you boxed then, this was during the Depression, you could get ten dollars if you won and seven and a half if you lost. So I did a lot of boxing.

The way I did my training was at noon at school; I would put boxing gloves on and take on anybody. I didn’t eat- I might grab a sandwich, and I must not have smelled too good for the afternoon school session. I knew a Richard Whitmore, who was one of the boys I got started with and he was a professional for some time. I don’t know what ever happened to him.

I actually did some amateur wrestling, too. I found out after I wrestled for quite awhile that in my fights I would knock people out. Evidently, I gained more muscle or strength or perhaps maturity.

I had not known about karate, tai chi, or any of these things, but I had heard of jujitsu. So, I began to learn some hand grips and things like that, I think coming out of this terrible feeling of being unable to help myself. None of us want to feel that way. Later, I went to California to box, and after joining the Marines, I was transferred to the Far East right out of boot camp on January 1, 1935. I went to the Philippines and did some boxing and took on everybody I could.

After being there for fifteen months, I was transferred to Shanghai in the fall of 1937. Shanghai was a center of this part of my life. There, I was first introduced to what was called Chinese Art. Sometimes people here call it Gung Fu or something of that kind. Anything Chinese style was referred to as Gung Fu Tze, which the Jesuits called Confucius. So, I think that is probably how the name Gung Fu Tze, came about. Chinese art, with the people I knew, called it Gung Fu.

In 1938, Mr. Lo Wei Doun took me to Wing On Hotel in Shanghai and let me see, for the first time, Chinese boxing. I don’t know how they could afford to take a beating like that to make a living. They would do two or three shows a day and they really hit one another. But at that time, people were starving and would do anything to get by. They had trained from very young boys and I was very impressed by it. Then Mr. Lo kind-of smiled at me and said, “Well, this is the externals of the art. It goes much deeper.”

He had been working for the International Police, he was an educated man, an official, and at one time worked for the Fire Department at the International Settlement in Shanghai. He was a master of the Chinese Art and did some marvelous things that were almost unbelievable at the time. I was interested in boxing, and so was Mr. Lo. He was also interested in cowboys and I know he wanted to be a cowboy.

He wouldn’t teach me the hatchet, even though he was a great hatchet man. In almost complete darkness he could throw these hatchets about 100 feet and hit a target, like a man’s head, with great accuracy. He had them under a quilted shirt. He could really whip them out. He would not teach me because he said, “You don’t want to spend all this time learning obsolete weapons. You have your trusty six shooter, what do you want to fool around with a little hatchet for?”

He could jump and grab, climb right up the sides of buildings. He could go over walls that had broken glass set in concrete on the top of them. I asked him what about dogs down there? He said, “If a dog attacks me, that’s his bad fortune.” He was a Chinese gentleman who was very humble and very deadly.

He also had a sense of humor that we could understand. This was one of the unique things about him. He was a broad-minded man. He said he believed there was one point where Christianity was superior to Buddhism, and that was that God should not expect a man to endure more than one wife at a time. Then, I met another Chinese Master that was quite different from Master Lo. We think of Chinese Art as being like soft karate, very evasive, and much of it is, but this man had hands which were so beaten up that they were nothing but clubs. He evidently worked with a concrete makiwara or something. He was a knot of muscle. I know he had a great reputation there in Shanghai. I didn’t do much studying with him. I probably should have, but I was still after the money I could get from boxing.

Actually, at that time, I did a little bit of judo at the downtown YMCA in Shanghai. I remember I met the great tennis player, Bill Tilton, and some other athletes who would travel through at the time. We trained in the racecourse. If you talk about Shanghai of the day, that’s where society met. The YMCA was right across from it. So, we would do our roadwork at the racecourse.

Now the Chinese boxers were the ones that caused what we call the Boxer Rebellion, in response to their nation being overrun. Europeans and Japanese had taken over the country. The Chinese didn’t have any modern weapons, but they had courage. It was almost miraculous how they, practically unarmed, could hold off the most modern armies in the world at the time.

So, I tried to study as much as I could, then I left China. I sought for a long time, kept practicing self defense arts. I began to find out my health was better, my courage was better, I wasn’t scared. There was something going on in me besides the physical things that I had learned. I began to grasp something we try to find and know we can find in the arts: serenity. There is something that happens to the character and personality.

In Peoria, 1960, I met Master Koeppel. He had been studying in Japan and in Hawaii. I wanted to learn what he knew. He was a purple belt at that time. We had a school there – part of the time it was just he and I. Then some other students joined, some of whom are still with Master Koeppel. We used to workout for four hours, and when we left, we did well just to walk. Both of us were having problems, so much of it was drowning our troubles in fatigue. Then he went to Chicago and taught in school there. He had a job running a trucking company. So, I had the school in Peoria on my own, taking over his students and mine.

We realized that we didn’t know as much as we wanted to. I was trying to recall all that I had learned. In those days, you didn’t have a smorgasbord of martial arts that you could go and pick information from. It was so hard to find knowledge. I practiced all I could. I had a hodgepodge of the whole thing and was working it the best I could. It was a lonely time for me.

I know I have injuries today that would not have occurred if I would have had a Sensei all through those years to warn me, as I warn my students. You don’t press the body in certain unnatural ways. I was going to force myself to do it. My cardiologist has said I have trained myself over the years to ignore pain. As a result, I had a heart attack and didn’t know it. While giving me the stress test, they asked me, “are you hurting?” and I said, “No”. He said, “The damage was there, but you have learned to ignore the pain,” which is good and bad because pain warns us of certain things.

Anyway, I was teaching there in Peoria. We would pick anybody’s brain. We would go anywhere where anybody claimed they knew anything about the art, stay there a couple days, and then learn all we could. We might pass on a little of our knowledge in exchange. I’d come back, Master Koeppel and I would look it over, teach it and see if it fit in.

I would like to name the people that I learned from in those days. I remember one of the most helpful people was Walter Todd, who lived across from San Francisco, I owe a lot to him. He was a man of great knowledge. He is an eighth degree karate master, and a judo master.

I also studied judo under Neil Rosenburg, in Milwaukee. I was one of the charter members there at the new YMCA, he would teach there. He came to visit our class here at one time. I had not done any judo, just a little in Shanghai. He said I amazed him, how strong and how I did it, he didn’t know. Of course, I had the training in martial arts before, but I didn’t say anything about it.

Then there was Master Trias. Master Koeppel sent some films to Master Trias, where he was doing some kata and wazas. Master Koeppel was a high kicker. I would never have been able to compare to his kicking. He doesn’t kick that high now, but of course he is more powerful and accurate than he was. Beautiful high kicks. He was not very old at the time. Master Trias was very interested in Master Koeppel. It came out that he got his shodan, from the films, correspondence, and so forth.

I didn’t go through the same procedure, so I got no rank at all. Master Trias didn’t even know I existed until later. I went to Phoenix and studied a little with him. I owe quite a bit to Master Trias, although right now, we don’t follow the same course. Now, he has become more interested in sport karate, which is not karate at all in my opinion. Not long after Master Koeppel made shodan, I did. He recommended me and got a group of people together.

We found some karate people quite good in the Chicago area. We hadn’t known they existed. The first Yudansha Kai in the State of Illinois was formed in my house in Peoria in 1963. We formed a black belt association – we were pioneers. We began to hold shiais (tournament). I used to be around shiais more than I am now. Billy, my son, was a star at it. He would seemingly win in kata and kumite wherever he went, and he was just a young kid. The first national shiai we had was in Chicago. I couldn’t be there because I had injured my knee. They asked Billy to give the opening prayer, which he did.

I appreciate having a Sensei. I appreciate so much that Master Koeppel shared and grew with me. We worked out when nobody else would. I remember we had some people come in off the street and they would test us. We would show them what we could do. He would do it one time, then I would another. That didn’t last very long. We would show people that this worked.

I have been working out and grabbing knowledge all the time, through time, I have been able to take some things and discard others that didn’t seem to be harmonious. One of the things that I have learned is you can know 50 kata, 3000wazas and not ever grasp what karate is about, but if you learn the principles of karate, then you can judge a kata, or a waza for a violation. If they do not follow the physical and physiological principles of the art you know something is wrong.

If you practice karate and do not know the principles, you get a lot of good exercise and learn some discipline; probably it won’t work if you have a real competition on the street and have decided to defend yourself. But if you know the principles, they have been tried and true. Not only can you do it in unarmed combat, but these principles apply in armed combat, such as the stick techniques that we do.

Another thing I have learned is that as you get older you don’t necessarily get weaker. You will get weaker in some things, but if you keep at it you will gain other strengths that will take their place. I was never a high kicker and cannot kick as high as I once could, but I am accurate and really have more power. I doubt I could lift the weights I once could, but my explosive power is greater. I can break more than I ever could. Part of this is psychological, a spiritual power we don’t fully understand. Another thing I have found is that your hands will keep getting faster if you keep practicing. I am 73 and I expect, in a few years, my hands to be faster than they are now. You can’t keep from getting old, but as we get older we gain things if we try. That is the reason the great masters could perform so much. Many of them were old men, but they were certainly not helpless old men.